[Expanded and updated version of a talk given at UC Berkeley, December 2, 2014.]

I have long been an alarmist about US-Russia relations. While the relationship has seen its ups and downs, I believe the trend has been decidedly negative since the mid-1990s. I’ve also long worried about a possible clash with Russia over NATO expansion, and particularly so after the Bush Administration decided to press – albeit unsuccessfully – America’s NATO allies to offer Ukraine and Georgia Membership Action Plans at the March 2008 Bucharest NATO summit.

Moreover, my Chicken Little view is that Moscow’s relationship with the West today is as dangerous as it was during the early years of the Cold War, and for similar reasons. Like then, the rules of the game and the border separating respective spheres of influence are unclear and contested. Which is why, in brief, we have the current crisis in Ukraine.

Finally, it is important to appreciate that a war with Russia could be every bit as catastrophic as a military conflict with the Soviet Union might have been in the early 1950s. Russia today has far more nuclear weapons than the Soviet Union did then – around 2,000 operational battlefield nuclear weapons, and many thousands more in storage. It also has some 500 strategic launchers and 1,700 deliverable nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States. And it has a large and modern conventional military equipped with a great many sophisticated weapons.

As a result, a military confrontation between NATO and Russia – even a low-level one precipitated by some kind of accident – would entail the same kind of game of chicken, and the same risks of escalation, as Cold War standoffs like the Berlin airlift, the Berlin Crisis of 1961, and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Mishandling Russia

I also believe that the West has contributed to the current crisis. In saying this, I am not arguing that the West is solely, or even mostly, to blame. But I believe the West has mishandled Russia, and that its post-Cold War Russia policy has been unwise and insufficiently risk averse. There has been too much hoping for the best and not enough planning for, and trying to avoid, the worst.

President Clinton signs NATO enlargement treaty, May 21, 1998, bringing in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary

In particular, the United States and its allies made two fundamental, and very consequential, mistakes in Russia policy after 1991. The first was to try to build a post-Cold War security architecture for Europe around NATO expansion. I felt then, and still feel, that it would have been wiser to try to create a European-wide security structure that included Russia – for example, by turning the OSCE, and the other institutions that emerged from the so-called Helsinki process, into a meaningful security organization. If that effort failed, or perhaps in conjunction with it, carefully measured NATO expansion might have been warranted. But no such effort was made.

The second, and related, error was a failure to appreciate just how illiberal, and alienated from the West, Russia was becoming, and to take steps to head off a confrontation before the current crisis. “Illiberal,” I should emphasize, is the appropriate term here, not “undemocratic.” One can argue about whether Russia is in some sense “democratic” — certainly a significant majority of Russians supports both the regime and the current leadership. The real problem is that Russia has become deeply illiberal, and as a result deeply anti-Western and, even more so, anti-American.

At any rate, I believe Western decision makers have been tone deaf about Russia – slow to recognize, or politically unwilling to acknowledge, the extent to which illiberalism, resentment of the West, and growing power were making a clash with Moscow increasingly likely and increasingly dangerous. That should have been made very clear by the 2008 Russia-Georgia War, which I thought then and think now was mostly about Russian objections to NATO expansion. Unfortunately, Western leaders lacked the strategic vision, and the political commitment, needed to avert what has turned out to be an acute geopolitical crisis.

If the first error was mostly Washington’s, the latter was mostly by the U.S.’s European partners, particularly Germany, where the consensus was that relations were fine, that deepening economic ties would placate Moscow and gradually make Russia “European,” and that the EU’s Eastern Partnership program would be viewed as benign by the Kremlin. For European officials speaking the cautious and diplomatic language of the EU, hard power was no longer an important factor in interstate relations in Europe. That, I believe, was and is naïve, and it is one of the reasons why the West failed to get Russia right, and address Russia’s security concerns, before it was too late.

Why the crisis is so dangerous

As to why the crisis is so dangerous, I would emphasize two factors. First, I do not agree with the conventional wisdom that ideology is not driving the conflict. On the contrary, my view is that it involves a fundamental clash of principles – or if you prefer, a clash of worldviews. And second, I believe there is an unstable balance of military power along Russia’s western borders that increases Moscow’s incentives to use force.

Prior to the annexation of Crimea, the contending principles were what I call the “Great Power Realism” of Russia, on the one hand, and “Democratism” in the West on the other hand.

Russian Great Power realism begins with a predicative claim that we are transitioning from an international order dominated by a single superpower, the United States, to a multipolar one in which power is increasingly distributed among a number of more-or-less equal “Great Powers.” This prediction is accompanied by a deeply held normative belief that the world will be better off for it. Russia will be, and should be, one of those Great Powers, and as a Great Power it will have, and should have, its own sphere of influence in its “Eurasian” neighborhood. The West should respect Russia’s rights as a Great Power, and it should avoid meddling in Russia’s internal affairs or in the internal affairs of states in Russia’s sphere of influence. Above all, it should cease efforts to draw those states into the Western orbit and to expand the EU, and especially NATO, to Russia’s borders.

Democratism is embraced with at least as much conviction by the West. It holds that every country has a right to be, should be, and can be democratic; that every state, and especially every democratic state, has a right to determine its own external orientation and alliances; and that the West has no right to prevent any country from joining the European institutional order if it meets Europe’s criteria.

Above all, it would be contrary to the West’s democratic values to cede any country, including Ukraine, to Moscow simply because that is what the Kremlin wants, regardless of the preferences of that country’s government and people.

With the annexation of Crimea, there is now another, yet more fundamental principle at stake for the West, a principle that it considers the foundation of a rule-governed international order and of post-World War II European security: there can be no changing of borders of internationally recognized states, especially in Europe, by force.

These contending principles, and the emotions they elicit on both sides, are why backing down for either side is going to be extremely difficult, perhaps even impossible.

The second reason the crisis is so dangerous is the unstable military balance along Russia’s western borders. The fact is that Russia has a great preponderance of military force along those borders, and as a result NATO is now overextended.

Regardless of what one thinks of NATO expansion, it was particularly risky for NATO to take in members that bordered on contiguous Russia (that is, excluding Kaliningrad). Even more risky was the decision to take in members that NATO could not credibly defend, or that it could not credibly defend without taking steps to establish a tripwire type of deterrence – for example, by placing US and NATO troops in harm’s way in militarily vulnerable countries.

Regardless of what one thinks of NATO expansion, it was particularly risky for NATO to take in members that bordered on contiguous Russia (that is, excluding Kaliningrad). Even more risky was the decision to take in members that NATO could not credibly defend, or that it could not credibly defend without taking steps to establish a tripwire type of deterrence – for example, by placing US and NATO troops in harm’s way in militarily vulnerable countries.

As it happened, NATO accepted two very small, and very vulnerable, countries that border on Russia – Estonia and Latvia. And it accepted a third – Lithuania – that does not share a border but is proximate to Russia and is also small and militarily highly vulnerable. In none of these cases did NATO make the hard choice of establishing a meaningful military deterrent as part of the accession process.

As a result, we are now in a situation where NATO’s Article 5 obliges all NATO-member-states (albeit somewhat ambiguously) to come to the collective defense of any other member-state if attacked. But it is very difficult to see how the West could do so were Estonia and Latvia to be invaded by Russia quickly and in force.

Moreover, there is a risk that we will find ourselves in the kind of competitive mobilization game over the Baltics that helped precipitate World War I. Consider what might happen next year when Russia undertakes, as planned, large-scale military exercises in its Central Military District, and masses troops in the vicinity of the Baltic states. By then, the U.S. and other NATO countries will have prepositioned significant military hardware in the Baltic states, and new rapid reaction forces will be available for deployment in response to the Russian troop presence exercises. Their purpose is to serve as a deterrent to a Russian invasion, so NATO presumably would order their deployment. And that, in turn, would give Moscow cause, and an excuse, to act preemptively.

The problem, in short, is that Putin and his advisors may conclude that the West has neither the power nor the will to dislodge a Russian army that quickly occupies Latvia and Estonia, that has tactical nuclear weapons at its disposal, and that is backed by Russia’s strategic nuclear arsenal. And the Kremlin may also conclude that NATO would collapse if Western governments and publics turn out to have very different tolerances for risking war with Russia should it attack Estonia and Latvia.

I should make clear that I am not saying that NATO membership is not an important deterrent – it is, and it is easy to understand why Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are very relieved to be part of NATO today. But the efficacy of that deterrent is limited, and the incentives to preempt by Moscow significant.

Finally, it is worth considering possible answers to the question of how Putin would react if the West crosses an implied Kremlin redline – say, by providing lethal weapons to Ukraine, by discussing NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia, or by placing ground troops, armor, or aviation permanently in the Baltic states.

I do not think Putin is so reckless as to risk outright war with the West, but he might be, and particularly so if the Russian economy completely tanks and he feels politically cornered. It is important to appreciate that Moscow may react asymmetrically to perceived threats from NATO – for example, it might respond to a U.S. decision to arm Ukraine with military pressure on Georgia, or by organizing or encouraging cyber-attacks on Western governments or, more likely, businesses.

At any rate, my view is that it would be extremely irresponsible for Western leaders to proceed as if a small risk of a catastrophic event is not worth worrying about.

U.S. policy today: Four general points

Let me turn finally to the U.S. policy response to Russia’s role in the Ukraine crisis and begin with four general points.

U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland hands out cakes to Maidan protesters, Dec. 10, 2013

First, I think the Obama Administration has made mistakes in handling Russia and in responding to the Ukraine crisis – for example, Victoria Nuland’s appearance on the Maidan in support of the opposition to Yanukovich, and Obama’s uncharacteristically gratuitous comment about Russia being a “regional power” that was acting out of weakness rather than strength. Nonetheless, I think much the most important mistakes in U.S.-Russia policy predate this administration, and that Obama has been, and will continue to be, appropriately cautious in reacting to the crisis and in dealings with Russia generally. As I just suggested, Russia is not Iraq, and a military confrontation with Moscow is more dangerous by orders of magnitude.

As a result, while the Administration has been clear in his opposition to the annexation of Crimea and the Kremlin’s destabilization of eastern Ukraine, Obama has avoided responding by grandstanding, or with hyperbole and personal attacks on Putin (unlike many in Congress). He has worked with Washington’s key allies to maintain a united front vis-à-vis Russia, notably on a sanctions regime, and he has slowly and quietly taken important steps to reinforce deterrence on NATO’s eastern flank, including in the Baltic republics (which I will discuss in a moment). All this, I believe, reflects a prudent response to a dangerous crisis, the seeds of which were sown long before he came into office, and where U.S. hard power options are limited.

Second, while a Republican-majority Senate will mean increased pressure on Obama to be tough with Moscow, I think the Administration will resist that pressure as long as the violencein eastern Ukraine does not escalate and Moscow does not ratchet up military pressure on Georgia, Moldova, or the Baltic republics, or engage in even more dangerous acts of brinkmanship with NATO.

Third, I believe that the mood of the American public is going to help Obama keep congressional hawks in check. There is little public appetite for making any real sacrifices, or taking any real risks, in Ukraine, especially military risks.

As suggested in the next slide, which is from a Chicago Council of Global Affairs survey published earlier this year, support for foreign activism has fallen significantly since Obama came into office, particularly among Republicans and Independents.

As suggested in the next slide, which is from a Chicago Council of Global Affairs survey published earlier this year, support for foreign activism has fallen significantly since Obama came into office, particularly among Republicans and Independents.

Public support for the use of force in response to the Ukraine crisis is likewise low, as shown in the next slide from the same survey. Note that only 42-44% of those surveyed support military action if Russia were to invade the Baltic states, and even fewer – some 27-32% – support a military response to a Russian invasion of Ukraine.

That said, I would not take this to mean that the U.S. would fail to respond militarily if the Baltic republics actually were attacked by Russia. I think it would. Public opinion can change rapidly, especially if American troops were to be killed as a result. I also believe that the U.S. political elite takes the country’s Article 5 obligations very seriously. But what is not clear is how Washington would respond, or whether other members of the Western alliance would live up their Article 5 obligations.

That said, I would not take this to mean that the U.S. would fail to respond militarily if the Baltic republics actually were attacked by Russia. I think it would. Public opinion can change rapidly, especially if American troops were to be killed as a result. I also believe that the U.S. political elite takes the country’s Article 5 obligations very seriously. But what is not clear is how Washington would respond, or whether other members of the Western alliance would live up their Article 5 obligations.

Nonetheless, Republicans will ramp up criticism of Obama’s foreign policy in the remaining two years of his presidency, and particularly so in anticipation of a Hillary Clinton presidential run in 2016. But I expect the president to continue to avoid being drawn into expensive and ineffectual military conflicts. With respect to Ukraine, the objective will be to do what is possible to help Kyiv economically and militarily – more on this in a moment – and to increase deterrence on NATO’s eastern flank, but to do so without provoking military escalation by, or direct confrontation with, Moscow.

Fourth, the United States is facing many serious foreign policy challenges other than Ukraine. Iraq, Syria, Iran, ISIS, China, economic weakness in Japan, and Europe’s Euro and growth crises are all competing for White House attention, and that is not going to change over the next two years. This, too, makes it more likely that the Obama Administration will respond carefully and deliberately in Ukraine.

Three key policy decisions

So let me turn to three key policy arenas for Washington: (1) sanctions on Russia; (2) assistance to Ukraine (including military assistance); and (3) reinforcing NATO’s eastern defenses.

- Economic sanctions on Russia

This is not the place to discuss the efficacy of sanctions, but let me simply state that I think that Western governments, and especially Washington, will find it politically difficult to lift those sanctions.

Once imposed, sanctions are typically difficult to lift – consider American sanctions on Iran. But that will be particularly true for sanctions on Russia because of the annexation of Crimea. Had Crimea not been annexed, a compromise might be possible based on a ceasefire in the Donbas and some kind of autonomy for Crimea, along with guarantees that Ukraine and Georgia would not join NATO. (Even this would have been hard for Western governments to swallow, however, because that is what more-or-less happened in Georgia after 2008, and Western governments would be reluctant to ignore Russian military intervention in a neighboring state a second time.) A compromise along those lines might in turn have provided Western governments with the political room needed to lift some, most, or even all sanctions.

The annexation of Crimea, however, makes it hard to imagine Western governments, Washington in particular, agreeing to business as usual with a government that has occupied and annexed the territory of a European sovereign state. That is particularly true given the many international agreements Moscow violated by its actions in Ukraine, including the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, the UN Charter, the Helsinki Accords, and the Black Sea basing agreement with Ukraine, to name but a few. As a result, it would be a major domestic political challenge, particularly in Washington, to sell some kind of “grand bargain” with a government that had so clearly violated previous international legal commitments.

In short, I think sanctions will remain in place for years, at least for the most part, even if we see a ceasefire take hold in the Donbas.

- Assistance to Ukraine

I believe the Obama Administration is going to continue to provide economic assistance to Ukraine and to support assistance from its allies, the IMF, and other multilateral institutions. However, that support is going to fall far short of what is needed to prevent real hardships for Ukrainians over the coming winter, and indeed for at least the next two or three years.

That is true for many reasons, but three particularly important ones are, first, the extent of Ukraine’s needs; second, concerns about Ukraine’s ability to make good use of significant economic assistance without major radical internal reforms; and third, public skepticism in the United States, including among Republicans, about the efficacy of economic assistance. The lingering effects of the Great Recession mean than the U.S. public is not in a particularly generous mood at present. Moreover, Ukraine’s economic needs should be seen in the context of other major international economic demands on Washington, including very serious economic problems in Europe and Japan.

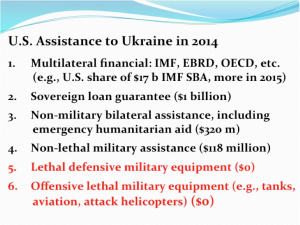

As a result, I expect more of what we have witnessed to date, which is modest direct economic assistance from Washington and indirect support through multilateral institutions, above all the IMF. As shown in the next slide, this year Washington has supported multilateral assistance, particularly through the IMF; provided Kyiv with a $1 billion sovereign loan guarantee; and ponied up $312 million in direct non-military aid. My guess is that these amounts will increase somewhat next year, and may continue if Ukraine engages in the kind of radical internal reforms that Georgia embraced after its 2003 Rose Revolution.

As a result, I expect more of what we have witnessed to date, which is modest direct economic assistance from Washington and indirect support through multilateral institutions, above all the IMF. As shown in the next slide, this year Washington has supported multilateral assistance, particularly through the IMF; provided Kyiv with a $1 billion sovereign loan guarantee; and ponied up $312 million in direct non-military aid. My guess is that these amounts will increase somewhat next year, and may continue if Ukraine engages in the kind of radical internal reforms that Georgia embraced after its 2003 Rose Revolution.

That said, I don’t mean to imply that economic assistance from the United States, IMF, the EU, and other foreign sources is not important to Kyiv – it is, indeed critically so. Without it, default on Ukraine’s foreign debt is certain, and economic hardships will be much worse. But foreign assistance is not going to turn the economy around quickly, particularly given Moscow’s very considerable economic leverage over Ukraine. It is accordingly going to be viewed as inadequate by the Ukrainian public. Indeed, some Ukrainians will eventually blame the IMF, and the West, for making matters worse, just as the Russian public viewed similar assistance to Russia in the 1990s as inadequate and foreign lenders and governments the cause of hardship rather than relievers of pain.

This brings me to the controversial question of U.S. military assistance to Ukraine. Washington provided $118 million in non-lethal military assistance to Kyiv in 2014, including night vision goggles, body armor, helmets, military binoculars, counter-motor radar systems, and small craft, as well as increased military training and advising.

This non-lethal assistance is also likely to increase, perhaps significantly, next year because the Administration will want to deflect pressure from Congressional hawks to provide lethal assistance.

While this has not been made public to my knowledge, I also suspect that Washington has also been providing, and we will continue to provide, Kyiv with important military intelligence.

The key debate in Washington, then, is about whether to give or sell lethal weapons to Kyiv, such as anti-tank weapons and shoulder-fired anti-aircraft (MANPADs). Congress has been considering a number of bills in support of Ukraine, including the “Ukraine Freedom Assistance Act,” which cleared the Senate Foreign Relations Committee unanimously on September 18. It requires the president to apply sanctions on certain Russian companies and amends the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 to designate Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova as “major non-NATO allies for purposes of that Act and the Arms Export Control Act.” It also “authorizes the president to provide lethal military assistance to Ukraine,” as follows:

Providing defense articles, defense services, and training to the Government of Ukraine for the purpose of countering offensive weapons and reestablishing the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine, including anti-tank and anti-armor weapons; crew weapons and ammunition; counter-artillery radars to identify and target artillery batteries; fire control, range finder, and optical and guidance and control equipment; tactical troop-operated surveillance drones, and secure command and communications equipment. It authorizes $350 million in fiscal year 2015 to carry out these activities.

On December 4, 2014, the House approved Resolution 758 that, among other provisions, “calls on the President to provide the Government of Ukraine with lethal and non-lethal defense articles, services, and training required to effectively defend its territory and sovereignty.”

The key words here, however, are “authorizes” and “calls on.” Neither the Senate bill nor the House resolution compel the president to do anything, and Obama would likely veto – successfully – a bill that made him take significant steps that he thinks contrary to U.S. national interests.

Accordingly, unless the war in eastern Ukraine escalates significantly, I think Obama is going to resist pressure to provide lethal equipment to Kyiv. And if he does decide to go forward with it, it will be limited. As Obama has repeatedly argued, U.S. anti-tank and other defensive weapons are not going to allow Ukraine to take back all of the Donbas or Crimea by force. They might, however, provoke Moscow into invading or attacking Ukrainian military assets much more aggressively, including assets well behind Ukrainian lines, using aviation and cruise or even ballistic missiles.

Finally, a quick word about Ukrainian membership in the EU and NATO.

Washington will continue to support Ukrainian membership in the EU, but Ukraine’s acute economic crisis and deeply rooted governance problems mean that actual membership is at best years down the road.

As for NATO, I do not believe there is any chance – full stop – that Ukraine will be asked to join unless Ukraine exercises de facto sovereignty over all of its territory, including Crimea. That is not going to happen for a very long time, if ever. Article 5 means that Ukrainian accession would effectively put NATO at war with Russia. No American president, no matter how hawkish, could believe that going to war with a nuclear-armed Russia was worth the benefits of bringing Ukraine into NATO.

Moreover, accepting new members requires unanimous approval by all NATO member-states. [Correction from original post – addendum below.] I suspect that there are far more member-states that would veto Ukrainian accession than member-states that would support it were it to come to a vote. And I suspect that that is what French President Hollande told Putin at the airport in Moscow earlier this week.

- Reinforcing NATO’s eastern defenses

Even before NATO’s September summit in Wales, the U.S. and its NATO allies were taking steps to increase the alliance’s land, navel, and air forces along NATO’s eastern borders.

Canadian Air Force fighter CF-18 Hornet (L) and Portuguese Air Force fighter F-16 patrol over Baltics air space, from the Zokniai air base near Siauliai, Lithuania (Reuters)

Among other measures, NATO reinforced its Baltic Air Patrol (the number of rotational fighter jets has gone up from 4 to 16). Those jets, which had been stationed in Lithuania, have begun using airfields in Estonia and Latvia. NATO naval vessels also increased patrolling in the Baltic and Black Seas (albeit in the latter case in compliance with the limitation of the Montreux Convention). And NATO stepped up military exercises, training, and rotational forces in the eastern member-states, and kept AWACs surveillance planes on constant patrol over Poland and Romania to monitor Russian and separatist military movements.

Significant additional measures were agreed to at the Wales Summit. The Alliance formally adopted a “Readiness Action Plan” that calls for increased defense spending and for “a more balanced sharing of costs and responsiveness.” Those member-states that are spending less than 2% of GDP on defense, and of that less than 20% on procurements, are supposed to reach those targets within a decade as “economic growth improves.” While it is unlikely that these norms will be met by all NATO members, there will likely be a slow but steady increase in military expenditures across the Alliance, and particular increases in defense spending by NATO’s eastern members.

In addition, NATO agreed to improve its existing Rapid Reaction Force by establishing a new “Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF),” which is slated to be in place by the end of 2015. Comprised of some 3,000 to 4,000 troops, initially from Germany, Denmark, and Norway, it is designed to be deployable within days. The Alliance also agreed to establish permanent command and control facilities in the east, and to continuously rotate forces on the territories of the “eastern Allies” (Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania) through 2015.

Separately, Britain, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Norway also announced plans to form a non-NATO Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) before 2018.

Meanwhile, the U.S. military has taken a number of its own “assurance” and “deterrence” measures in the east. It has increased military assistance to NATO’s eastern member-states, including increased training exercises and interoperability assistance. “Rotational” U.S. Army small units are to remain in Poland and the Baltic states at least until next year and perhaps beyond. (These troops would then “rotational” only in the sense that they would not use permanent bases, with all the associated costs, including family housing, and would be in theater for relatively brief periods before being replaced.)

Meanwhile, the U.S. military has taken a number of its own “assurance” and “deterrence” measures in the east. It has increased military assistance to NATO’s eastern member-states, including increased training exercises and interoperability assistance. “Rotational” U.S. Army small units are to remain in Poland and the Baltic states at least until next year and perhaps beyond. (These troops would then “rotational” only in the sense that they would not use permanent bases, with all the associated costs, including family housing, and would be in theater for relatively brief periods before being replaced.)

Doubtless most alarming to Moscow, however, are U.S. plans to keep a third “Brigade Combat Team” (BCT) in Europe on a “permanent rotational” basis (the other two are truly “permanent” in the sense they are based in Europe). The additional armored BCT will conduct regular exercises with the U.S. European allies for the time being, although Moscow will doubtless assume, with reason, that they may at some point engage in exercises in Ukraine and Georgia as well.

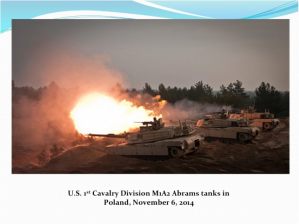

In early October, the nature of these plans was fleshed out when the Army announced that it was assigning the 1st Brigade Combat Team of the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division, the home base of which is Fort Hood, Texas, to the U.S. European Command. Elements of the brigade arrived in Europe with armor in November and took part in military exercises in Poland and the Baltic states that lasted into December (see photo).

In early October, the nature of these plans was fleshed out when the Army announced that it was assigning the 1st Brigade Combat Team of the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division, the home base of which is Fort Hood, Texas, to the U.S. European Command. Elements of the brigade arrived in Europe with armor in November and took part in military exercises in Poland and the Baltic states that lasted into December (see photo).

The Army has since announced that it is prepositioning 50 U.S. armored vehicles, including U.S. M1A2 Abrams Main Battle Tanks and Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicles, in Poland and the Baltic republics – which is to say, tanks and IFVs shipped in November are going to remain in theater after the troops return to Texas (it being very expensive to ship armor from Texas to Latvia). The Army has since announced plans to preposition an additional 100 U.S. armored vehicles in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and/or the Baltic states by the end of 2015.

Finally, other NATO member states, including Great Britain, have also significantly increased their military presence in the east. In early December, NATO announced that its member-states had conducted over 200 exercises in Europe in 2014, including exercises involving 2000 British and Polish troops in Poland from late October to early December; 6,000 troops from nine NATO countries in Estonia in May; 2,000 troops from ten NATO countries in the Baltics, Germany, and Poland in September; and 2,280 troops from nine NATO countries in Lithuania in November.

The October through December exercise in Poland involved 20 British Challenger 2 tanks (see photo), along with other armored vehicles from the U.K.’s 3rd Armored Division. The Polish forces included 56 of Poland’s modern, German-made Leopard 2 tanks.

Not surprisingly, the Kremlin views these moves as extremely provocative. If the Kremlin believed that NATO expansion was a vital security threat before the buildup, it is going to believe the threat is considerably greater now. What is unclear, however, is what Russia can do about it.

For the time being, the primary response has been brinkmanship, particu larly but not only along NATO’s frontiers. The nature of this brinkmanship was described at length in a November 10 report from the European Leadership Network, entitled “Dangerous Brinkmanship,” that detailed some 40 “incidents involving Russian and Western militaries and security agencies” over the past eight months. The bulk of the incidents have occurred in Baltic Sea, as shown in the slide. While the report avoids directly blaming Moscow for the incidents, it calls on the Kremlin to “urgently re-evaluate the costs and risks of continuing its more assertive military posture,” and on Western governments to try to persuade Russia “to move in this direction.”

larly but not only along NATO’s frontiers. The nature of this brinkmanship was described at length in a November 10 report from the European Leadership Network, entitled “Dangerous Brinkmanship,” that detailed some 40 “incidents involving Russian and Western militaries and security agencies” over the past eight months. The bulk of the incidents have occurred in Baltic Sea, as shown in the slide. While the report avoids directly blaming Moscow for the incidents, it calls on the Kremlin to “urgently re-evaluate the costs and risks of continuing its more assertive military posture,” and on Western governments to try to persuade Russia “to move in this direction.”

This brinkmanship makes the crisis in Russia’s relations with the West all the more dangerous. A single incident, even if unintentional, could escalate into a broader confrontation. In engaging in these acts, the Kremlin is signaling that it is extremely concerned about its deteriorating security env

This brinkmanship makes the crisis in Russia’s relations with the West all the more dangerous. A single incident, even if unintentional, could escalate into a broader confrontation. In engaging in these acts, the Kremlin is signaling that it is extremely concerned about its deteriorating security env

ironment. It is also signaling that it has a higher tolerance for risk than the West.

Beyond that, Moscow is going to build up its own military assets along its western borders, notably in Crimea, Kaliningrad, and Belarus. And it may at some point withdraw from the INF Treaty and deploy nuclear-armed ballistic and cruise missiles that target Western Europe.

Conclusion

I believe that this crisis started out dangerous and has since become more dangerous. A military confrontation between NATO and Russia is not a remote possibility. Early on, before the annexation of Crimea, I thought that statesmanship might produce a “grand bargain” entailing formal neutrality for Ukraine and Georgia, along with conventional and nuclear arms control agreements. Unfortunately, I believe that the annexation of Crimea has effectively taken that option off the table, at least for the next two or three years.

The essence of the problem, as I see it, is that the West cannot give the Kremlin what it wants, which is (1) Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova within Russia’s sphere of influence; (2) acquiescence to Russia’s annexation of Crimea; and (3) no movement of NATO or U.S. forces towards its borders.

Accordingly, I believe we are in for more of what we have seen in recent months. The West will keep its economic sanctions in place – indeed, it is more likely to deepen those sanctions than to lift them. It will continue to try to support Ukraine economically and politically, although that support will fall well short of solving Ukraine’s internal problems, which ultimately can only be addressed by Kyiv. It will continue to provide non-lethal military assistance to Ukraine, and at some point the U.S. may begin providing lethal defensive weapons. Finally, NATO will continue to build up its military presence on its eastern flank.

The Kremlin will respond with economic and military pressure on Ukraine, as well as on Georgia, Moldova, the Baltic states, Finland, and Sweden; with a military buildup on its Western borders; and with continued acts of brinksmanship with NATO. It will also respond asymmetrically to what it considers provocations by the West, including cyber-sabotage (and not merely cyber-espionage). It will make renewed efforts to solidify its ties to Belarus, Armenia, the Central Asian states, China, and other countries that it sees as standing up to the West. And it will try to position itself globally as the leading champion of resistance to Western liberal hegemony, to weaken the West politically and economically, and to promote divisions within NATO and the EU.

How we get out of this lose-lose game is not clear, at least to me. And unfortunately I suspect it is going to last for years. What is critically important, however, is that at some point Moscow and Washington begin to discuss measures that make a military confrontation less likely, just as Moscow and Washington did after the Cuban Missile Crisis.

[Correction: The original post stated that NATO accession required a treaty amendment. That was not quite correct. The accession process is governed by Article 10 of NATO’s 1949 founding treaty, which reads: “The Parties may, by unanimous agreement, invite any other European State in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area to accede to this Treaty.” The way this has worked out in practice is accession requires unanimous approval by the governments of all member-states, as expressed through a vote in the North Atlantic Council, the Alliance’s principal political decision make body. Individual member-states, however, have different procedures for ratifying and amending treaties, as well as difference understandings of whether accession requires the same procedures for ratifying accession of new NATO members. The U.S. position has been that accession is in effect a treaty modification and requires the same two-thirds vote in the Senate as treaty ratification.]

Pingback: La caída del precio del petróleo, ¿una estrategia geopolítica? | noticias de abajo

Pingback: The Oil Price Crash Of 2014 — Jamiatul Ulama KZN

Pingback: Richard Heinberg: The Oil Price Crash of 2014 | The Benicia Independent