Yesterday, Ukrainian President Poroshenko read a brief statement at the Kyiv airport in which he announced that the Ukrainian forces in and around Debaltseve, whose main line of retreat to the north, the M03, had come under the control of the separatists a week or so earlier, had been ordered to break out and make it back to Ukrainian controlled territory. According to Poroshenko:

We can say that 80 percent of troops have been already withdrawn. We are waiting for two more columns. Warriors of the 128th brigade, parts of units of the 30th brigade, the rest of the 25th and the 40th battalions, Special Forces, the National Guard and the police have already left the area…. I can say that despite tough artillery and MLRS shelling, according to the recent data, we have 30 wounded out of more than 2,000 warriors. The information is being collected and may be clarified.

It is not yet clear how severe the Ukrainian losses have been from the operation. While many Ukrainian troops managed to make it out, they were fired upon as they were withdrawing. There are also at least some pockets of Ukrainian troops still caught behind enemy lines. (Moscow News reported continued shelling in Debaltseve last night). One thing that can be said with certainty is that final casualty figures are going to be much higher than Poroshenko admitted to in his statement. Kyiv announced today that it had confirmed 13 killed in action, 157 wounded, 90 prisoners of war, and 82 missing. I would be very surprised if those figures did not increase dramatically, particularly the figure for KIAs, based on journalists’ interviews with those who made it out. It is worth noting that Poroshenko mentioned 2,000 Ukrainian “warriors” in Debaltseve. It is possible that he was referring only to those who made it out, the implication then being, when combined with his claim that 80% had made it back to Ukrainian lines, that there had been around 2,600 Ukrainian troops in the pocket before the breakout. Ukraine’s ATO press service, in a separate statement today, referred to 2,459 soldiers who had escaped. It therefore appears that the size of the Ukrainian force in Debaltseve was smaller than the media had been claiming – around 3,000, rather than the usually cited estimates of 5,000 to 8,000). It is also less than the figure Putin cited when he referred to Debaltseve in his post-negotiation remarks in Minsk last week. At any rate, if the casualty figures Kyiv is citing are close to accurate, my take is that Kyiv is fortunate that the scale of its military defeat in Debaltseve was not much worse. If there had indeed been 6,000 to 8,000 Ukrainian troops trapped there, and if they had been held hostage by the separatists (which is what I thought would happen when I posted my “Ukrainian hostage crisis” post several days ago), Kyiv would have been between an even bigger rock and an even worse hard place than it is now. Losses from the breakout by the forces that were there could also have been much greater had the separatists completely surrounded them in force.

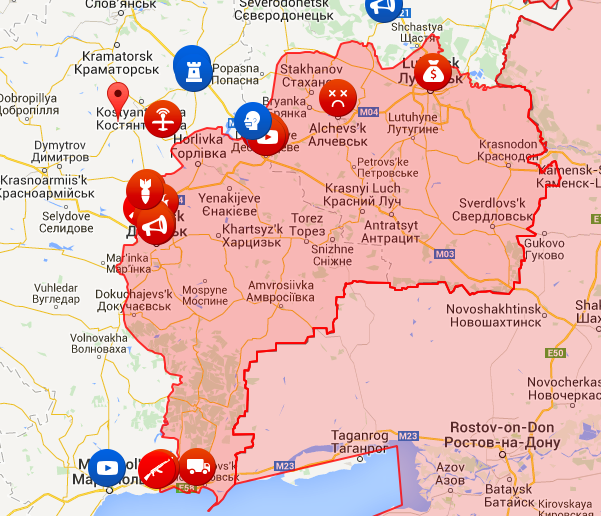

Maps from several weeks ago. Debaltseve pocket evident in last map. Since eliminated, and Ukrainians pushed back elsewhere as well..

Nonetheless, this is a major defeat for Ukraine, particularly in view of the fact that their losses since the withdrawal began were only a portion of total losses in the area in recent weeks. The separatists also now control an important transportation hub between their two “capitals,” Donetsk and Luhansk. A hostage crisis, or an even bigger military defeat, would have undermined Poroshenko’s political position in Kyiv even more than the withdrawal will, which is going to be bad enough for him. (Today there are reports that Ukraine’s volunteer battalions announced that they will set up a separate command headquarters in Dnipropetrovsk, which could prove a major headache for Kyiv and the Ukrainian central command in the coming months.) As an aside, it is worth asking why the separatists did not try to keep those troops hostage but instead decided to drive them out and inflict as heavy losses on them as possible in the process. Obviously they decided to remove the pocket as quickly as possible rather than keeping the Ukrainians trapped, which would have forced Kyiv to negotiate a withdrawal. But I am not sure why. One possible answer is that the separatists, supported by the Kremlin, wanted to achieve some limited military objectives quickly before accepting a ceasefire and a more-or-less frozen conflict (see below). A less benign possibility is that they wanted to achieve those limited military objectives as quickly as possible before moving on to a more ambitious military campaign, and to do so before increased Western military assistance to Kyiv begins to make a difference on the battlefield. At any rate, in my view Poroshenko had no choice but to order a fighting withdrawal. Indeed, I think he should have done so much earlier. He and his military advisors probably should never have tried to defend the Debaltseve salient in the first place, given the obvious risk that doing so posed to the Ukrainian forces there. That said, the separatists have yet to achieve what I have been referring to as their immediate military objectives (see the map below for the general areas where fighting is still underway).  I am sure that the separatists will move quickly to clean out the remaining Ukrainian forces in Debaltseve very rapidly. They may then press ahead to the north, the goal being to establish new defensive lines between the Vuhlehersk and Myronivske reservoirs (see below), which would mean trying to take the towns of Luhanske (not the city, but a smallish town) and Svitlodarsk. They are also trying to take more ground to the east of Horlivka and Donetsk, as well as the territory lost last week to Ukrainian forces near Mariupol.

I am sure that the separatists will move quickly to clean out the remaining Ukrainian forces in Debaltseve very rapidly. They may then press ahead to the north, the goal being to establish new defensive lines between the Vuhlehersk and Myronivske reservoirs (see below), which would mean trying to take the towns of Luhanske (not the city, but a smallish town) and Svitlodarsk. They are also trying to take more ground to the east of Horlivka and Donetsk, as well as the territory lost last week to Ukrainian forces near Mariupol.

In any case, I believe we are now at a major milestone in the current war. There is still a chance that, once the separatists have attained their immediate military objectives, the fighting winds down. If, however, the Kremlin decides that the separatists, perhaps supported more-or-less openly by Russian regulars, should press ahead with a major new offensive, we are likely to see heavy fighting for months to come, and indeed quite possibly into next year. That would almost certainly lead the United States, supported by some but probably not all of its allies, to substantially increase military assistance to Kyiv. (There are actually many options for providing a great deal of military assistance to Kyiv that do not entail the United States providing lethal weapons, notably Javelin anti-tank weapons – a topic I will take up in a future post.) Importantly, however, the separatists announced today that, having taken Debaltseve, they are prepared to implement a ceasefire. If they do indeed cease firing, either immediately or after achieving their limited objectives, there is a chance for a frozen conflict that brings an end to most or even all fighting (see below). So where do we go from here? I see five possibilities.

- A stable frozen conflict

This would require the separatists to implement a unilateral ceasefire and then agree (perhaps not immediately) that OSCE monitors and/or possibly a U.N.-mandated armed peacekeeping force oversee a separation of forces and a buffer zone. That will only be possible, given the new facts on the ground, if Ukraine accepts (de facto, if not formally), a new line of demarcation. It will also only be possible if Ukraine accepts a Russian contribution to a monitoring or peacekeeping force (as unpalatable as that would be for the Ukrainians). It will also be politically difficult for Western governments to support a settlement based on yet another line of demarcation after the failure of Minsk I and Minsk II. Nevertheless, if the fighting winds down and Kyiv supports some kind of ceasefire and separation of forces, it is likely that Western governments would go along and help implement it. Still, it is difficult to see how they can really negotiate over a new demarcation line with Moscow at this point. Indeed, it may be that a political settlement is really only possible if Washington and Moscow engage in direct negotiations over a broad security arrangement that extends well beyond Ukraine. But doing so would be very difficult for the Obama Administration to sell domestically. Still, if we did get a stable frozen conflict, the separatists, and Moscow, would be in a position to try to restore order, address the ever-deepening humanitarian crisis in the east, and repair the devastated economy in the region they control. It would likewise give Kyiv some breathing room to deal with Ukraine’s acute economic problems. I continue to believe that this would be the least-worst option for Kyiv. But I also continue to doubt that it is what we will get, because I do not believe the Kremlin sees a stable frozen conflict as satisfying the geopolitical objectives that have been driving its Ukrainian policy (see many of my earlier posts, e.g., “Reading Russia on Ukraine”). And as I just suggested, it will be difficult for Western governments to support a settlement based on a post-Debaltseve line of demarcation, or to come up with some kind of credible formula for claiming the “Minsk process” is still in effect.

- An unstable “frozen” conflict (“frozen” in the sense of prolonged but without an effective ceasefire and separation of forces agreement)

The separatists would announce a ceasefire on condition that the Ukrainians cease firing as well, but there would be no new separation of forces agreement and an international monitoring mission or peacekeeping force. In effect, the separatists would defend the territory they control by force of arms.

- A grinding war of attrition

Under this scenario, the separatists would continue to press forward, gradually and at various points, and with various degrees on intensity, along the line of contact. The result would be a war of attrition, the intent of which would be to maintain heavy pressure on Kyiv and the West but without greatly increasing Russian military exposure in the conflict. If this is where we go, the level of violence will be largely driven by whether the separatists decide to assault cities such as Mariupol, Kramatorsk, Slavyansk, and Artemivsk (where most of the troops that retreated from Debaltseve regrouped). Assaults on significant urban areas would almost certainly be long and bloody affairs with significant civilian casualties.

- A Russian offensive to establish a land corridor to Crimea

If the Kremlin decides that the gains are worth the risks and costs of trying to establish a land corridor to Crimea, I believe that would likely require open Russian involvement – so an end to even a pretense of non-involvement by Moscow.

Rough indication of the length of the very long front line (some 900 km) if Russia pushes for a land corridor to Ukraine

It would also mean either bypassing and besieging Mariupol, or assaulting it. Mariupol is a significant city, with a population of some 500,000 before the war began. And the Ukrainians have had months to build up their defenses there. Keep in mind that the Russian army had to destroy Grozny, which by then had a civilian population of under 100,000 and was defended by probably around 2,000 Chechen rebels, to take it at the beginning of the second Chechen war. Also consider that the only significant urban area in the current war taken by force was Slavyansk last summer, which had a population of a little over 100,00 before the war and was defended by a relatively small number of separatists. The Ukrainians had to pound the city for weeks before driving the separatists out. Finally, as the map above suggests, consider the length of the line of contact after a land corridor campaign would entail — it would be roughly twice as long as it is now, and it would have to be defended. In short, trying to take Mariupol by starving it out or assaulting it as part of an effort to establish a land corridor would entail many civilian casualties and urban warfare in Mariupol. It would therefore constitute a dramatic escalation by Moscow. It would also expose separatist and Russian forces to counterattacks along the long line of contact. And it would virtually guarantee a full-blown proxy war with the West. For all these reasons, I continue to doubt that it will happen. But it might.

- A major Russian assault on Ukraine’s war fighting assets

A final option, which I think is even less likely than the land corridor possibility, is a Russian attempt, sooner to later, to seriously degrade Ukraine’s war fighting abilities by striking deep into Ukrainian-held territory. That might mean a Russian ground invasion from the north and south to cut off Ukrainian forces in the east (that I think would be a very risky military undertaking for Russia, however), or more likely it might mean an extended aerial and stand-off missile campaign like the one waged by NATO against Serbia in 1999, targeting not only military assets but also economic infrastructure such as bridges, roads, railroads, and even factories. Russia does not have the same ability to carry out an extended precision aerial campaign in Ukraine that NATO had in Serbia, and Russia would also suffer much more serious losses than NATO suffered in the Serbia campaign. But it would be extremely damaging nonetheless. At the least, it would make an economic recovery in Ukraine even more difficult, greatly complicate Western efforts to help Kyiv, and further weaken an already weak and struggling state. It is also, with the possible exception of a crisis in the Baltic republics, the most likely path toward a direct confrontation between Russia and NATO.

*****

I think the least-worst outcome for all parties, including Russia (although I doubt that the Kremlin agrees), is Scenario 1 (a stable frozen conflict). Scenarios 4 (the land corridor) and 5 (a Russian assault on Ukraine’s war fighting assets) will make a prolonged proxy war in Ukraine almost certain. Scenario 5 will also significantly increase the risk of a military confrontation with NATO. Scenario 3 (a war of attrition) will very likely produce a proxy war as well, but likely a less intense one than Scenarios 4 and 5. Scenario 2 (an unstable frozen conflict) will likely lead Washington and some of its allies to gradually increase military assistance to Ukraine, but perhaps without crossing Moscow’s fuzzy redline regarding “lethal” assistance from Washington. I believe which option is selected is mostly in the hands of one man, Vladimir Putin, which is one reason why the situation is so dangerous. A misjudgment by Putin could lead to a devastating proxy war in Ukraine, the primary victim of which would be Ukraine and its people. It could even lead an armed conflict with NATO. My guess is that the most likely scenarios are 2 or 3. But all are possible. And I am also sure that no matter what happens with respect to the war in eastern Ukraine, Moscow is going to continue to apply heavy pressure on Kyiv, other neighboring governments, and the West in an effort to reverse what it sees as a deteriorating geopolitical position.

Pingback: Apocalypse not now: Why the direct war between Russia, NATO is unlikely | Timber Exec