While the Kremlin’s long-term objective in Ukraine has been, and remains, the country’s integration into a Russian-dominated Eurasian Union, my guess is that its endgame in the current crisis is the establishment of a breakaway region in the east modeled on Transnistria in Moldova.

What follows is a review of Russia’s involvement in Transnistria, with a particular focus on Moscow’s prospects for maintaining its influence in the region in the wake of the Ukraine crisis and the signing of EU association agreements by Moldova and Ukraine last week (June 27). My next post will focus on the relevance of Transnistria to the uprisings in eastern Ukraine.

*****

The Prednestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR – “Prednestrovia”is the Russian equivalent of what the West has come to call “Transnistria” since the 1990s) is a self-declared but unrecognized polity that claims sovereignty over the left (east) bank of the Dniester (Nistru in Romanian/Moldovan) River and small parts of the right bank around the city of Bender (known to Moldovans as Tighina) in what the international community (including Russia, at least to date) recognizes as part of Moldova. The only entities that formally recognize Transnistria as independent are South Ossetia and Abkhazia, whose independence is recognized only by Russia and a handful of other states, and neither of which has a seat in the UN General Assembly. Nevertheless, with the exception of international recognition, Transnistria has all the attributes of statehood – constitution; legislative, executive, and judicial organs; a capital city (Tiraspol); a security apparatus; a national flag; and so on.

The Prednestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR – “Prednestrovia”is the Russian equivalent of what the West has come to call “Transnistria” since the 1990s) is a self-declared but unrecognized polity that claims sovereignty over the left (east) bank of the Dniester (Nistru in Romanian/Moldovan) River and small parts of the right bank around the city of Bender (known to Moldovans as Tighina) in what the international community (including Russia, at least to date) recognizes as part of Moldova. The only entities that formally recognize Transnistria as independent are South Ossetia and Abkhazia, whose independence is recognized only by Russia and a handful of other states, and neither of which has a seat in the UN General Assembly. Nevertheless, with the exception of international recognition, Transnistria has all the attributes of statehood – constitution; legislative, executive, and judicial organs; a capital city (Tiraspol); a security apparatus; a national flag; and so on.

Most of the approximately 550,000 inhabitants of the region (out of a total population in Moldova of 3.6 million) is Slavic by ethnicity (or “nationality” in Soviet discourse). According to a 2004 census, 30% of the population is Russian, 29% is Ukrainian, and a small percent is Bulgarian. Most of the remainder ( 32%) is non-Slavic Moldovan. Many residents have dual or multiple citizenship, including at least 150,000 (and probably more) with Russian passports. Russian is the language of public and private business, and Cyrillic is the predominant script even for Moldovan/Romanian, in contrast with Moldova proper, which has switched back to the Latin script. (Moldovan is in effect a dialect of Romanian, despite efforts by the Soviets and more recently Moldovan nationalists to accentuate differences and “construct” them as separate languages.)

32%) is non-Slavic Moldovan. Many residents have dual or multiple citizenship, including at least 150,000 (and probably more) with Russian passports. Russian is the language of public and private business, and Cyrillic is the predominant script even for Moldovan/Romanian, in contrast with Moldova proper, which has switched back to the Latin script. (Moldovan is in effect a dialect of Romanian, despite efforts by the Soviets and more recently Moldovan nationalists to accentuate differences and “construct” them as separate languages.)

Historical background

Transnistria was incorporated into the Russian Empire at the end of the 18th century after Russia defeated the Ottomans in one of the many Russo-Turkish wars in the era. As shown in the map to the right, administratively the region was made part of Novorossiya guberniya (governorship), which had been established several decades earlier and included much of present-day southern and eastern Ukraine. (Note, however, that Ukraine’s Kharkiv oblast and much of the Donbas were not part of Novorossiya.) Present-day Moldova, on the right bank of the Dniester, was part of the Principality of Moldavia, a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, when in the early 19th century the eastern portion of the territory between the Dniester and Prut rivers was incorporated into the Russian Empire. Thereafter, the territory became known as Bessarabia.

the era. As shown in the map to the right, administratively the region was made part of Novorossiya guberniya (governorship), which had been established several decades earlier and included much of present-day southern and eastern Ukraine. (Note, however, that Ukraine’s Kharkiv oblast and much of the Donbas were not part of Novorossiya.) Present-day Moldova, on the right bank of the Dniester, was part of the Principality of Moldavia, a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, when in the early 19th century the eastern portion of the territory between the Dniester and Prut rivers was incorporated into the Russian Empire. Thereafter, the territory became known as Bessarabia.

After the turmoil of the Russian Revolution and Civil War, Bessarabia became part of independent Romania. The Soviets took control of Transnistria and in 1924 made it part of the Moldovan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR), an autonomous area within the Ukrainian SSR and administratively subordinate to Kyiv. In 1940, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact allowed Moscow to seize Bessarabia, which was then joined with Transnistria to form the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic. The Soviets lost this territory to the invading Axis powers in 1941, but retook it in 1944, at which point the Moldovan SSR was reestablished, with the right-bank city of Chişinău (typically transliterated from Russian into English during the Soviet era as Kishinev) as its capital.

Perestroika, the Soviet collapse, and the establishment of the PMR

The upshot of this is that when the Soviet Union dissolved at the end of 1991, Moldova was one of the USSR’s fifteen union republics, and as such became one of the USSR’s fifteen successor states, each of which would become fully independent with a seat in the UN General Assembly. Without exception, each was also recognized on the basis of the external and internal borders of fifteen union republics inherited from the Soviet period.

For some of the successor states, however, the problem was that not all people, and not all regions, accepted the legitimacy of the new states and their claims to sovereignty over all their territory. As a result, wars broke out between the new national governments and separatists in Chechnya, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Transnistria. In each case, with the eventual exception of Chechnya, separatists prevailed on the battlefield but failed to win international recognition (with the partial, and recent, exceptions of Abkhazia and Ossetia noted above). The results are so-called “frozen conflicts” in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Transnistria.

In the Transnistrian case, its status as an unrecognized state is the product of a brief war between supporters of Moldova’s territorial integrity and separatists that broke out shortly after the Soviet collapse. Moldova, like many of the USSR’s union republics, experienced a wave of ethno-national mobilization in the Gorbachev era. A Moldovan Popular Front emerged and demanded, inter alia, that Moldovan/Romanian replace Russia as the state language of the republic, that the republic revert to the Latin script from Cyrillic, and that Moldovan/Romanian become the language of instruction in schools. Some also pressed for the reunification of Moldova and Romania. Eventually, Moldova’s nationalists demanded “sovereignty” (understood essentially as the right to determine the region’s status as independent or otherwise) and then full independence.

As in other union republics, nationalist mobilization by Moldova’s “titular nationality” (that is, Moldovans, whose position was that Moldova is the nation-state of the Moldovans) alarmed minorities, particularly Russians and Ukrainians. As in Ukraine, the further east one went in Moldova, the more Russified and Russophone (and the more pro-Soviet) the population. That was particularly true in Transnistria (see the map below). A political organization representing the Slavic and Russian-speaking peoples of the republic, called Unity (Yedinstvo), emerged to defend the interests of the country’s Russophones. It demanded equal status for Moldovan and Russian, agitated for the preservation of the Soviet state, and opposed Moldovan sovereignty and later independence.

Another minority group, the Gagauz, who speak a Turkic language but are Orthodox Christian, also mobilized in opposition to Moldovan ethno-nationalism at the time, but while there were episodes of violence between Moldovan and Gagauz nationalists, there was no full-blown war or the emergence of a breakaway region beyond the legal writ of the Moldovan central government. Instead, the Gagauz worked out a compromise (albeit a still precarious one) with Chişinău that established a Gagauz “semiautonomous region” in the south (see the first map above). Importantly, there were, and are, considerably fewer Gagauz than Transnistrians – less than 150,000, versus some 650,000 residents of Transnistria at the time (now down to 550,000 or less).

The first instance of significant violence between the mostly Slavic-speaking, pro-Soviet (later more-or-less pro-Russian, especially today) forces in Moldova and supporters of Moldovan sovereignty came in late 1989. Violence escalated over the course of the following year, with both sides arming themselves and volunteer militias forming in Transnistria. Transnistria declared itself sovereign in September 1990 and then fully independent in December 1991. The Moldovan parliament in Chişinău predictably responded by declaring both claims illegal.

The Transnistria War of March-June 1992

The so-called Transnistrian War, which led to an estimated 700 deaths, 100,000 displaced persons, and much destruction, broke out in the months following the dissolution of the Soviet state at the end of 1991. In March 1992, escalating violence in and around Transnistria led the Moldovan parliament to declare a state of emergency. The newly independent country’s president, Mircea Snegur, ordered his nascent, and weak, security forces to “liquidate and disarm the illegitimate armed formations,” an order they were unable to fulfill. He accused the separatists of trying to turn the region “into a militarist, Communist concentration camp.”

By then, separatist fighters from Transnistria were being joined by Cossacks, pro-Soviet volunteers, Russian and Ukrainian nationalists, and assorted “military tourists” and mercenaries in combating forces loyal to Moldova’s central government. Elements of what had been the Soviet Union’s 14th Guards Army, which had been stationed in the Moldovan SSR since the 1950s and which the Russian government unilaterally but successfully laid claim to in March 1992 (the 14th Army’s equipment on the right bank of the Dniester was transferred to the new Moldovan army), eventually joined the fighting on the side of the separatists. Snegur demanded that Russia withdraw the 14th Army from Moldovan territory, at one point going so far as to suggest that Chişinău might declare war on Russia if the 14th Army did not remain in its barracks, stop providing the separatists with arms, and redeploy to Russia.

As in other breakaway regions at the time, the role of Moscow in the Moldovan unrest was in fact rather murky and complicated. In the late-Soviet and early post-Soviet periods, most of the agitation in separatist areas coming from Moscow was by pro-Soviet conservatives who were political opponents not only of Gorbachev and his efforts to reform Soviet socialism but also of Yeltsin and his efforts to democratize and marketize Russia. After Yeltsin became Russia’s president in early 1991, Yeltsin made clear that he wanted to see an end to the violence in Moldova but did not want ethnic Russians and Russian speakers to be discriminated against.

Nevertheless, it was clear that most of the enlisted men, NCOs, and officers of the 14th Army sympathized with the separatists (some 80% of its soldiers and half of its officers were from Transnistria). As a result, they sold the PRM forces weapons, turned a blind eye to the looting of weapons depots, and occasionally provided the separatists with direct military support. Only at the end of the war, however, did the 14th Army, which was commanded by the future Russian presidential candidate, Gen. Aleksandr Lebed, openly engage Moldovan forces in an effort to end an offensive that might have led to a separatist rout. Even then it was not entirely clear whether Lebed was acting on Yeltsin’s orders or independently.

While the extent and character of Russian involvement in the fighting in Transnistria is unclear, what is clear is that the Yeltsin Administration played a key role in brokering a ceasefire. The ceasefire came into effect in late June 1992 after almost four months of war on the basis of an agreement signed by Yeltsin and his Moldovan counterpart. It provided for the establishment of a tripartite Joint Control Commission (JCC), made up of representatives from Russia, Moldova, and the PRM, that was charged with overseeing the agreement’s implementation. A joint peacekeeping force of Russian, Moldovan, and Transnistrian troops was also established to patrol a demilitarized zone along the Dniester River separating the warring parties (see right panel map above).

The agreement successfully brought an end to the fighting and remains in effect to this day. But it also left Moldova’s central government without any writ in Transnistria, which also remains the case to this day. And it left a particularly controversial legacy in the form of a continuing Russian military presence in Transnistria.

Russia’s military presence

Russia’s role in negotiating the ceasefire was generally welcomed by Western governments at the time – this was the “honeymoon” period of Russian relations with the West, when Andrei Kozyrev was Russian foreign minister and Western governments hoped that Russia would play a constructive role in supporting the sovereignty of the other Soviet successor states. Over time, however, Russia’s military presence in the region became increasingly controversial and a significant irritant in Russian relations with the OSCE, the EU, and the United States, relations that gradually deteriorated over the course of the 1990s and into the new millennium.

Under the terms of the 1992 ceasefire agreement, the 14th Army was allowed to remain in place but was required to observe strict neutrality. The actual number of Russian troops in the region continued to shrink, however, from an estimated 4,000 to 6,000 in 1995 to between 1500 and 2000 by the end of the decade. Of those, approximately 400 (the exact number varied) serve as the Russian contribution to the joint peacekeeping force (PKF), with Moldova and Transnistria contributing roughly the same number. Ten Ukrainians were added to the PKF as observers in 1998. The OSCE also has its own monitoring mission in the region, representatives of which participate in JCC meetings. Western governments regularly complain, however, that the OSCE monitors are frequently blocked from carrying out their duties by the PMR.

In 1995, the 14th Army was formally disbanded, and its remnants formed a new entity, the Operational Group of Russian Forces (OGRF) in Moldova, which reported to the Ministry of Defense in Moscow. Currently the number of Russian troops in Transnistria is estimated at 1200-1500. Those not assigned to the JCC’s PKF guard Russian weapons depots and other military installations.

For several years after the ceasefire went into effect, it appeared that Moscow might be willing to withdraw most if not all of its forces from Moldovan territory even in the absence of a political settlement between Chişinău and Tiraspol. This was particularly the case after Moldova agreed in April 1994, under pressure from Moscow, to join the Commonwealth of Independent States. That October, Moscow and Chişinău signed an agreement committing the Kremlin to withdrawing its remaining forces within three years after the agreement entered into force. To Chişinău’s surprise and consternation, the Kremlin subsequently took the position that the agreement had to be approved by its State Duma, which refused to do so. The agreement was thus never implemented, and Russian forces remained in place.

Transnistria, the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty, and the OSCE Istanbul Declaration

In the second half of the 1990s, the Russian military contingent in Transnistria became an increasingly important issue in negotiations over revisions to the 1990 Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) that limited NATO and Warsaw force disposition. The Warsaw Pact’s dissolution and NATO’s eastern expansion meant that restrictions on so-called Treaty Limited Equipment (TLE), notably tanks, armored combat vehicles, heavy artillery, combat aircraft, and attack helicopters, needed updating. Moscow was particularly interested in revising the so-called “flank limitations,” which restricted its ability to deploy TLE on its territory, in part because it was the only party to the treaty other than Ukraine that was restricted within its own territory. (These concerns were only partially relieved by amendments to the Treaty adopted in 1996). But the Kremlin was also concerned that the 1990 Treaty did not apply to some of NATO’s new members, notably Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

The revised treaty (referred to as the “Adapted Treaty”) was signed by Russia and the other CFE signatory states at an OSCE summit in Istanbul on November 18-19, 1999. The revisions replaced NATO-Warsaw Pact limits with national and territorial restrictions, the difference being the former limited TLE of national militaries only, while the latter restricted deployments by foreign powers. Russia and Ukraine continued to have sub-ceilings in specific areas of their territory. The treaty stipulated that it would come into effect after ratification by all thirty signatory states. Until then, the original treaty would remain operative.

In the period since, only a handful of signatories, one of which is Russia, has ratified the treaty. Not a single NATO member has done so. The key issue blocking ratification has been NATO’s insistence that Russia comply with commitments made in the Treaty’s Final Act and the Istanbul Summit Declaration to withdraw their troops from the territory of Moldova and Georgia.

The Final Act and Summit Declaration are essentially political statements, not legal ones, but they were signed by the head of Russia’s delegation, then Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov. The former includes a special statement by Moldova abjuring its “right to receive a temporary deployment on its territory” and welcoming “the commitment of the Russian Federation to withdraw and/or destroy Russian conventional armaments and equipment limited by the Treaty by the end of 2001, in the context of its commitment referred to in paragraph 19 of the Istanbul Summit Declaration.” The referenced paragraph reads as follows:

We welcome the commitment by the Russian Federation to complete withdrawal of the Russian forces from the territory of Moldova by the end of 2002. We also welcome the willingness of the Republic of Moldova and of the OSCE to facilitate this process, within their respective abilities, by the agreed deadline.

In anticipation of having to comply with the not-yet-ratified Adapted Treaty, Moscow began withdrawing or destroying TLE in Transnistria in 2000. In 2002, it claimed that it had met all TLE targets, including in Moldova. NATO concurred, but it insisted that Moscow had reneged on its commitment in the Final Act and Summit Declaration to withdraw from Moldova and Georgia. It also made clear that NATO members would not ratify the treaty until Moscow had fulfilled its Final Act and Summit Declaration commitments.

By then, Moscow was apparently having second thoughts about further withdrawals from Moldova and Georgia (assuming that it had signed the CFE Final Act and Istanbul Summit Declaration in good faith in the first place). It was also having second thoughts about the terms of the Adapted Treaty. No withdrawal took place, and no NATO member-state ratified the treaty.

On December 12, 2007, Russia announced that, because NATO governments had refused to ratify the Adapted Treaty, it was “suspending” implementation of the still-in-force 1990 Treaty, a stance that continues to this day. The Obama administration made a modest effort to save the Adapted Treaty in 2010, but discussions went nowhere. By then, the CFE process had been effectively derailed by Moscow’s intervention in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In November 2011, Washington announced that it would no longer allow Russian inspectors on US bases to monitor CFE compliance or provide Moscow with annual notifications and military data exchanges. Moscow’s annexation of Crimea, the destabilization of eastern Ukraine, and Russia’s Ukraine-related troop deployments have only made matters worse. The CFE is effectively dead, at least for the time being.

The Kozak Memorandum and Moscow’s “federalization” plan

Despite the controversy over Russia’s military presence in Transnistria, there have been continuous, but generally fruitless, international efforts to promote a political settlement between Chişinău and Tiraspol.

For our purposes, the most important development in the “peace process” came in November 2003 when Dmitry Kozak, a long-time advisor to Putin who is now one of Russia’s deputy prime ministers, proposed a plan for a final settlement. The essence of the so-called Kozak Memorandum (officially titled “Russian Draft Memorandum on the Basic Principles of the State Structure of a United State in Moldova”) was the transformation of Moldova into an “asymmetric federation” whereby Transnistria and Gagauzia would have extensive autonomy over their own affairs as well as veto power over constitutional amendments and the ratification of international treaties that might limit their autonomy. It also provided that Moldova would be a “neutral and demilitarized state.” From Moscow’s perspective, these latter powers were critical, because they meant that Transnistria alone, but even more so Transnistria and Gagauzia combined, could block membership in the European Union and NATO.

The memorandum called for a new constitution establishing a unique federation made up of three parts, “federal territory” (i.e., Moldova proper) and two “subjects of the federation” (i.e., Transnistria and Gagauzia). It specified the respective competences of the federal government, those of the constituent units of the federation, and those that would be shared by the center and those units. There would be a bicameral legislature, with a lower house elected by proportional representation.

Another key provision in the plan was the composition and powers of the upper house, to be called the Senate. There would be a total of 26 senators, thirteen of whom would be elected indirectly by the lower house, nine would be elected from Transnistria, and four elected from Gagauzia. That would guarantee Transnistria, which at the time had roughly fourteen percent of Moldova’s total population, at least 35% of Senate seats, while Gagauzia, with roughly four percent of the population, would have at least 15%. Together, Senators from Transnistria and Gagauzia would make up at least half of the Senate. Given that their electorate would vote in elections to the lower house, they would have some influence over the remaining seats as well.

With constitutional amendments and treaties requiring approval by a majority in the Senate, Moscow could be confident that Transnistria and Gagauzia could easily block EU membership, but it could be even more confident, given the provision that Moldova would be “neutral and demilitarized,” that the country would not join NATO for the foreseeable future. Moscow also indicated that it would, at the insistence of the PMR, maintain a military presence in the region for twenty years, thereby guaranteeing the agreement’s implementation.

Moldova’s president at the time, Vladimir Voronin, initially expressed support for the plan. Voronin, president from 2001 to 2009, had been the head of the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova since 1994, and he thus represented that part of the electorate that wanted to maintain good relations with Moscow. In the face of considerable domestic opposition to the Kozak plan, however, as well as opposition from Western governments and the OSCE, he ended up rejecting the proposal, arguing, inter alia, that Moldova’s constitution precluded the stationing of foreign troops on Moldovan territory.

For Washington and its European allies, a federation was fine as the basis for a settlement, including one that provided Gagauzia and Transnistria with extensive autonomy. (Gagauzia is currently designated a “semiautonomous” region of Moldova and already has extensive political autonomy). However, the country’s external orientation and alliances should be determined by the national government. In particular, they did not want to give Transnistria and Gagauzia the power to block gradual integration and eventual membership in the European Union. Neither did they want to accept the permanent existence of a more-or-less lawless entity on the EU’s periphery.

The Kozak Memorandum was a key item on the agenda of an OSCE meeting in December 2003. Disagreement over the plan between Moscow and Western governments contributed to the failure of the meeting to produce a Joint Declaration at its conclusion. Since then, Chişinău has been increasingly chary of federalization, and in 2005 its parliament adopted a law that effectively excludes it as a solution to the conflict.

That same year, a so-called “5+2” process for reaching a settlement began, with the OSCE, Russia and Ukraine as mediators, Chişinău and Tiraspol as the parties to the conflict, and the European Union and the United States as observers. The process has helped maintain the status quo, but there have been no signs of progress toward a final settlement.

Chişinău’s ambivalence

Responses in Moldova by ethnic group to the question: “If there were a referendum on Moldova’s accession to the EU/Eurasian Customs Union next Sunday which would you vote for?” (April 2014). Source: Ellie Knott and David Rinnert, http://bit.ly/1pSq4c7.

Although Chişinău continued to insist that it wanted to restore its sovereignty over Transnistria and that Russia withdraw all troops from Moldovan soil, it has been less than enthusiastic about the prospect (not unlike South Korea with respect to unification with North Korea).

One reason for this ambivalence is that Moldovan authorities fear that restoring sovereignty over the east bank would mean a significant number of new voters who did not support the construction of Moldova as the nation-state of ethnic Moldovans. They would also likely block Moldova’s efforts to join the EU and support closer economic and political ties to Russia. That most of the population of Transnistria is, and probably remains, strongly pro-Russian was suggested in 2006 when PMR organized a referendum in which 97% of those voting supported “independence from Moldova and free association with Russia,” as well as by the recent appeal of the region’s legislature to follow Crimea in joining Russia.

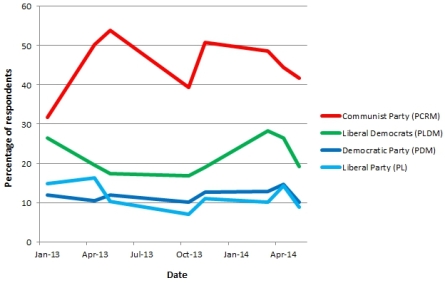

As in Ukraine, the Moldovan electorate has been divided on whether the country should seek to join the EU or try to maintain good relations with Russia and join the Eurasian Economic Union. The balance of political forces in Chişinău has been relatively even. The current pro-EU coalition government of Liberal Democrats, Democratic Party, and Liberal Party has a relatively narrow parliamentary majority, and it might well lose that majority to the less anti-Russian Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova in parliamentary elections this November. Adding Transnistria’s voters to the national polls would make the current governing parties’ electoral prospects worse in November and beyond. Moreover, as shown by the chart below, the country’s ethnic minorities are much more likely to oppose EU accession than Moldovan/Romanians, so pressing ahead runs the risk of aggravating ethnic tensions in the country.

Yet another factor behind Chişinău’s reluctance to move aggressively to reach a settlement with the PRM is that integration would likely be very expensive. Moldova is already Europe’s poorest country, and the national government does not want to take on the economic burden of subsidizing Transnistria’s uncompetitive enterprises – some 80% of the region’s economy comes from manufacturing, and most of that is in steel production, and Russia is its largest trading partner. Nor does Chişinău want to assume responsibility for Transnistria’s considerable external debt, most of which is the result of borrowing to cover natural gas deliveries from Russia.

Finally, Transnistria is notorious for its corruption, organized crime, and general lawlessness, even more so than Moldova proper. The Moldovan government and the Moldovan electorate worry that those problems would worsen considerably in Moldova proper in the wake of a settlement.

All of the considerations – the electoral impact of reintegration, the economic costs, and the effect on the rule of law in Moldova proper – complicate the country’s turn to Europe. On the other hand, a resolution of the conflict would make eventual full membership in the European Union more likely because the EU is reluctant to accept members that have unresolved internal conflicts and cannot successfully control their borders. That is even more the case with NATO.

Nevertheless, unwillingness to spend political capital in pursuit of settlement does not mean willingness to accept secession. Even less does it suggest a willingness to accept annexation by Russia. In this sense, it is no different than Russia with respect to Chechnya, Georgia with respect to Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and Azerbaijan with respect to Nagorno-Karabakh. Objectively, each of these countries would be politically, economically, and militarily better off allowing the separatists to go their own way, but subjectively the electorate in each country considers such a move almost unthinkable, and no government could survive if it proposed it. Canada’s willingness to countenance the possibility of the secession of Quebec, or the United Kingdom’s willingness to accept Scotland’s independence if it votes for independence later this year, is not an option in the ethno-national states of central and eastern Europe.

to spend political capital in pursuit of settlement does not mean willingness to accept secession. Even less does it suggest a willingness to accept annexation by Russia. In this sense, it is no different than Russia with respect to Chechnya, Georgia with respect to Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and Azerbaijan with respect to Nagorno-Karabakh. Objectively, each of these countries would be politically, economically, and militarily better off allowing the separatists to go their own way, but subjectively the electorate in each country considers such a move almost unthinkable, and no government could survive if it proposed it. Canada’s willingness to countenance the possibility of the secession of Quebec, or the United Kingdom’s willingness to accept Scotland’s independence if it votes for independence later this year, is not an option in the ethno-national states of central and eastern Europe.

A bridge too far?

Chişinău’s best hope for eventually reaching a settlement with Transnistria would be for EU integration to raise the standard of living in Moldova proper, while a pro-European government in Kyiv makes Russia’s presence in the PMR increasingly untenable. This outcome became considerably more likely after Moldova and Ukraine, along with Georgia, signed so-called Association Agreements and Deep and Comprehensive Free-Trade Agreement (AA/DCFTA) with the European Union on June 27.

Moscow no doubt assumes, in my view correctly, that Moldova’s integration into the EU will be increasingly difficult to derail over time. It must also assume that its position in Transnistria will become more costly and precarious if Ukraine also integrates successfully into the West. The obvious problem for Moscow is that goods, officials, soldiers, and military equipment passing from Russia to Transnistria (and/or back) have to transit Ukraine or Romania. Permission from both countries to do so is likely to become increasingly difficult, particularly for military assets.

Moscow’s best, and perhaps last, chance to keep Moldova out of the EU is therefore the Moldovan parliamentary elections in November. It is hoping for a victory by the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova, which if not pro-Russian is at least less hostile to Moscow and considerably less enthusiastic about EU accession. In the months leading up to the election, Moscow will do its best to convince the Moldovan electorate to vote for the Communists by making EU integration maximally painful, much more painful than joining the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union. There is also a small chance, particularly if the crisis in eastern Ukraine escalates and Russia sends troops across the border, that Moscow will make another out-of-the-box move by recognizing Transnistria’s independence, annexing it, or ignoring Ukrainian and Romanian efforts to deny Russian officials, soldiers, and military equipment access to their airspace.

Source: Ellie Knott and David Rinnert, LSE, http://bit.ly/1pSq4c7

Russia’s leverage in Moldova is still considerable, even if it is diminishing. The PMR remains extremely pro-Russian, anti-European, and anti-Chişinău. Tiraspol has repeatedly asked Moscow to allow it to join Russia, most recently on April 16. A large majority of the Gagauz is also pro-Russian and favors joining the Eurasian Customs Union rather than the EU. In February, a referendum in Gagauzia – which Chişinău considered illegal – showed overwhelming support among the Gagauz for closer ties to Russia and opposition to EU integration. And as noted earlier, the electorate as whole, at least until recently, has been divided over whether to embrace Europe and seek membership in the EU or whether to maintain good relations with Russia.

As for economic leverage, Moscow announced last year that it was embargoing wine imports from Moldova on the grounds that Moldovan wine did not meet Russian safety standards. (The fact that Moscow chose not to embargo wine from Transnistria made it abundantly clear that the move was made for political, not health, reasons.) Moscow has since suggested that it might also embargo Moldovan fruits and vegetables, which would be particularly painful because it is going to be difficult for Moldovan farmers to sell into the EU’s highly protected and regulated agricultural markets – and the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova, it should be noted, draws much of its support from the rural population.

Yet another measure under consideration by the Kremlin is limiting permits for Moldovans seeking work in Russia. It may also force Moldovan workers already in Russia to leave. Annual remittances from Moldovans in Russia are estimated at some $1 billion, and significantly reducing those transfers will make life even more difficult for already hard up Moldovans.

Finally, Moldova is already a sideshow in the Ukrainian-Russian natural gas dispute. The country gets almost all of its gas from Russia through Ukraine. In the past, Ukraine has helped ameliorate Russian pressure on Chişinău using gas deliveries by making up some of the shortfall, but that is going to be more difficult if Russia and Ukraine fail to resolve their dispute and the gas is not delivered over the winter. On the other hand, Transnistria gets its gas from Russia through Ukraine as well, and it will find it even more difficult to make it through the coming winter without assistance from Ukraine or Moldova proper.

Meanwhile, Moscow’s economic leverage over Moldova is declining. The Moldovan government, despite popular concerns about the economic consequences of deeper integration with Europe, has been steadily reorienting trade to the West. In 2013, the EU’s share of Moldova’s total trade was 54%, while with Russia it was only 12%. As shown in the chart to the right, total trade with the EU has been growing, while it has been decreasing with Russia.

Meanwhile, Moscow’s economic leverage over Moldova is declining. The Moldovan government, despite popular concerns about the economic consequences of deeper integration with Europe, has been steadily reorienting trade to the West. In 2013, the EU’s share of Moldova’s total trade was 54%, while with Russia it was only 12%. As shown in the chart to the right, total trade with the EU has been growing, while it has been decreasing with Russia.

Chişinău has also been taking steps to limit Russia’s economic influence in Transnistria. In December 2005, Chişinău and Kyiv signed an agreement requiring all Transnistrian companies (many of which are entirely or partially Russian-owned) that export into or through Ukrainian, notably goods destined for Russia, to register with Moldovan authorities. The agreement came after Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution brought a pro-Western government to power in Kyiv, and after a Border Assistance Mission from the EU arrived in Moldova and Ukraine to help Chişinău and Kyiv control their borders and limit smuggling operations in and out of Transnistria. Kyiv followed up by introducing new customs regulations on its border with Transnistria in early 2006.

Tiraspol and Moscow responded by characterizing these measures as an “economic blockade” that was creating a “humanitarian disaster” in Transnistria. This did not stop the PRM from retaliating by blocking trade with Ukraine and Moldova. Given its location, however, this would have meant effective autarky for the region, and the PMR’s counter blockade was quickly lifted. Exports from Transnistria nonetheless declined, and the Ukraine crisis has only made Transnistria’s economic isolation worse. Trade is being hurt in the first place by Ukraine’s economic freefall.

But in addition, fearing border provocations or the participation of Russia’s Transnistrian troops in a possible invasion, Kyiv has taken more steps to police its border. While the border is not closed, checkpoints have been set up that discourage carriers from delivering the goods, and there are reports that exports from the region have already fallen 30-40% and may fall further. Transnistria is particularly dependent on the importation of food products from Ukraine, and it can expect an even more miserable winter if food as well as natural gas imports are seriously disrupted.

Meanwhile, Chişinău has been trying to convince the people of the region that they, too, can benefit from European integration. As of April 28, Moldovans with biometric passports have been allowed to enter the 26 countries of the EU’s “Schengen Group.” In May, the number of Moldovans traveling to the EU increased by some 20 percent over the same period last year. Although Tiraspol insists, convincingly, that the people of the region remain staunchly pro-Russian and anti-EU, visa-free travel to Europe may help ameliorate tensions and reduce hostility over the long run.

Moscow’s increasingly precarious position in Transnistria was highlighted by an unusual diplomatic incident last month involving Moscow’s point man on the conflict, Dmitry Rogozin. Rogozin is a former Russian ambassador to NATO, one of two Russian deputy prime ministers, and Putin’s special envoy to Transnistria. He is also known for his undiplomatic language and his contempt for Washington, the EU, and Western liberalism. Suffice it to say that he does not speak “European.” He is also currently on the EU’s (as well as US’s, Canada’s, and Australia’s) post-Crimea sanctions list, which among other consequences bans him from traveling to EU countries or through EU airspace.

On May 9, the date most Soviet successor states celebrate as the anniversary of Germany’s surrender in World War II, Rogozin traveled to Transnistria, where he presided over a military parade, met with the PMR leadership, and promised Russia would continue to defend the people of Transnistria. While the exact facts are murky, it appears that upon departing Tiraspol for Moscow, his plane was denied permission to fly through Romanian airspace. (Romania, as a member of the EU, was presumably enforcing the EU travel ban.) The plane then tried to return to Russia through Ukrainian airspace but was intercepted by a Ukrainian fighter and forced to land in Chişinău. Rogozin managed to make it to Moscow on a commercial flight, but the plane was detained in Chişinău, which allowed Moldovan officials to confiscate a petition with some 30,000 Transnistrian signatures asking Moscow to annex the region. In Moscow, Rogozin tweeted the following about the incident: “Upon US request, Romania has closed its airspace for my plane. Ukraine doesn’t allow me to pass through again. Next time I’ll fly on board TU-160.” (The TU-160 is Russia’s largest strategic bomber.)

If nothing else, the incident highlighted the extent to which Russia’s position in Transnistria is in trouble. At some point, Ukraine and Romania may deny Moscow the right to use their airspace to deliver troops or military supplies to the region. Moscow would then be faced with a Hobson’s choice of either accepting a humiliating stand-down or trying to resupply its forces illegally (presumably through Ukrainian rather than Romanian airspace, given the latter’s NATO membership), with all the attendant risks of a possible military confrontation.

*****

Moscow’s leverage over Moldova will likely continue to wane – geography will prevail, it seems. Had Transnistria shared a border with Russia, or even with Belarus, it would likely have taken the path of North Ossetia and Abkhazia and become an unrecognized dependency of Moscow. Given that it was once part of Novorossiya, it might even have been annexed, like Crimea. But the fact is that Russia cannot get to Moldova, or Transnistria, without first going through Ukraine or Romania.

Russia’ s influence in Moldova, and its role as the external defender of Transnistria, has been facilitated until recently by Kyiv. In the post-Soviet era, Kyiv has had a series of more-or-less pro-Russian governments, the principle exception being during the Viktor Yushchenko presidency, when the government was weak and ineffectual. Many Ukrainians, including many Ukrainian nationalists (notably, for example, Ukrainian Cossacks) have been sympathetic to the mostly Slavic speakers of Trasnistria – indeed many of the outsiders who assisted the Transnistrian rebels during the 1992 war were Ukrainian. For the most part, Kyiv has tried to avoid provoking Moscow by making life more difficult for the breakaway region or for Russian troops in Transnistria. Given the extent of the current hostility in the country to the Russian government, the people of Russia, and Putin personally, that is likely to change, as the Rogozin incident highlighted.

Moreover, the credibility of Russian levers of influence over Moldova – and to some extent over Russia’s other neighbors as well – has been compromised by the signing of the AA/DCFTAs by Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia. It would be an exaggeration to say that Russia used all the arrows in its quiver to prevent those agreements from going forward, but it clearly used many, including the annexation of Crimea and the destabilization of eastern Ukraine. In Moldova’s case, Moscow’s wine embargo failed to get Chişinău to change course, despite the fact that Russia has historically been a critical market for Moldovan wine producers. Neither did threats of other economic sanctions. It is also unlikely that Russia can do much to destabilize the frozen conflict in Transnistria, given the limited size of its military contingent there and the difficulties it would face trying to build it up in the face of opposition from Ukraine and Romania, not to speak of the EU, OSCE, NATO, and Washington.

This is not to suggest that the Kremlin has given up on Moldova. On the contrary, we are very likely heading, unfortunately, into a long period of confrontation between the West and Moscow over the external orientation of Russia’s western neighbors. The contest is going to be waged with economic, informational, and military instruments, although hopefully that later will not include outright war.

But of the countries that the Kremlin would like to integrate into the Eurasian Union, Moldova is the less likely to do so. The Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova is a weak reed for Moscow to rely upon, and in any case it may not prevail in November. Moscow’s influence will weaken further if, in the relatively near future, the EU decides to offer Moldova a firm date for membership. And at some point down the road, depending on how Russia’s relationship with the West develops, Moldova may well be accepted into NATO.

Pingback: Move over the Donbass, new fault lines are in sight. | Checks&Balances

Pingback: Russian Foreign Policy and Propaganda

Pingback: The Frozen Conflict in Transnistria – Russian Bear