Note to readers: I plan to start blogging again, having recently retired from UC Berkeley and relocated to New York City. I will start with an exercise in empathy (which is different from sympathy), or if you prefer, red teaming or devil’s advocating (to coin a term). Specifically, I will try to imagine how a Putin advisor would likely assess Russia’s economic, political, and foreign/security circumstances on the eve of Putin’s all-but-certain reelection on March 18.

The main point of the exercise is to try to mitigate my own confirmation and preference biases, as well as those of other Western Russia watchers, many of whom suffer, in my view, from wishful thinking.

To be clear, I doubt some of the imagined advisor’s sanguine assessments, particularly on the foreign policy/security front. But I suspect it is the way that Putin and his kommanda see things. And it is why I think the Kremlin is unlikely to change course significantly, if at all, after March.

The advice takes the form of three memos (posts) from this advisor to Putin. I begin with a post on the economy. The next post will address domestic politics and regime stability. The final post will take up foreign and security policy.

None of the facts adduced in the series is intentionally inaccurate, although a great many facts are left out.

***

Our economy is recovering after two years of contraction following the oil price and sanctions shocks of 2014. After declines of 2.8 percent and 0.2 percent in 2015 and 2016, respectively, growth should come in at about 1.7 percent in 2017, or perhaps a little higher. The economy is expected to pick up this year, with most forecasts predicting growth of 1.5 percent to two percent, and then a little over two percent over the next several years. There is a reasonable chance that the economy will do better than consensus forecasts. A November 2017 analysis from Goldman Sachs predicted the economy would grow at 3.3 percent in 2018 and 2.9 percent in 2019.

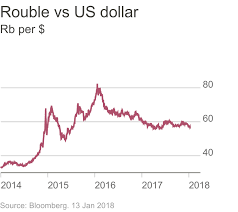

The economy continues to benefit from sound macroeconomic management. In particular, we can thank the Russian Central Bank (RCP) for allowing the ruble to decline significantly and rapidly against the dollar and other major currencies after the 2014 shocks. Real wages declined and those on fixed incomes and consumers in general suffered, but as in the past the decline in real wages meant employment held up. Most importantly, we avoided a prolonged recession, and the recession we did have would likely have been much more acute had the RCB tried to defend the ruble (a lesson we learned the hard way in 1998).

The economy continues to benefit from sound macroeconomic management. In particular, we can thank the Russian Central Bank (RCP) for allowing the ruble to decline significantly and rapidly against the dollar and other major currencies after the 2014 shocks. Real wages declined and those on fixed incomes and consumers in general suffered, but as in the past the decline in real wages meant employment held up. Most importantly, we avoided a prolonged recession, and the recession we did have would likely have been much more acute had the RCB tried to defend the ruble (a lesson we learned the hard way in 1998).

With the return to growth, the RCB has begun focusing on reducing inflation, which is expected to come in at under four percent for 2017, less than half of the rate in 2016 and well down from the post-2014 peak of 15 percent. The RCB expects it to remain in the four percent range for 2018.

The ruble has strengthened considerably since its low in February 2016, when it fell to over 78 against the dollar. It is now at 56 to the dollar, and since April 2017 it has remained within a band of roughly 56 to 61.

Lower inflation and the stable ruble have helped consumption, which is particularly good news as we head into the March presidential elections. The RCB expects private consumption to strengthen further in 2018.

We have also responded to the 2014 shocks with prudent fiscal policies. After being almost in fiscal balance in 2012, 2013, and 2014, we ran modest deficits of 2.4 percent in 2015, 3.5 percent in 2016, and 1.5 percent in 2017. (check). Spending has focused on major infrastructure projects, including the bridge to Crimea across the Kerch Strait, the “Power of Siberia” gas pipeline to China, and soccer stadiums for the World Cup, which we will host this year.

Running modest fiscal deficits during a period of economic weakness was the right move, but if oil prices hold up, we expect the deficit to decline further in 2018, and with luck we may see a small surplus this year for the first time since 2011.

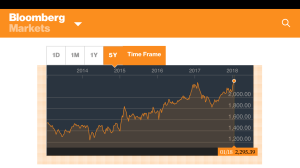

In our fiscal planning for 2017, we conservatively assumed an oil price of $40/bbl of Brent crude. Brent prices in fact averaged well above that overthe year. It is now around $70/bbl, up from a low of around $45/bbl in June. While the American shale revolution should prevent another surge in oil prices, we expect strong global growth to help keep oil prices relatively high. Despite Western sanctions on our oil and gas sectors, we expect production and exports to hold up as well, including exports to EU countries, particularly after the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline comes on-line in 2019.

In our fiscal planning for 2017, we conservatively assumed an oil price of $40/bbl of Brent crude. Brent prices in fact averaged well above that overthe year. It is now around $70/bbl, up from a low of around $45/bbl in June. While the American shale revolution should prevent another surge in oil prices, we expect strong global growth to help keep oil prices relatively high. Despite Western sanctions on our oil and gas sectors, we expect production and exports to hold up as well, including exports to EU countries, particularly after the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline comes on-line in 2019.

External debt as a percentage of GDP is 40.1 percent, which is very manageable and low by international standards, much lower than the external debt of our former partners in the G-7.

Our international reserve funds have held up well, despite claims by critics that our responses to 2014 would soon exhaust them. They fell from $538 billion in 2012 to $385 billion at then end of 2014, but reserves have since stabilized and are beginning to grow again. In September, Fitch revised its outlook for our sovereign debt from stable to positive. And once again foreign investors have been bullish on Russian government bonds – they now own some 30 percent of our sovereign debt, up from 5 percent in 2016.

While the ruble-denominated MICEX Russian stock index rose only slightly in 2017, it’s up some 100 percent since early 2015. We also continue to attract some foreign direct investment, although FDI fell in 2017 compared to 2016 and is well down from pre-2014 highs.

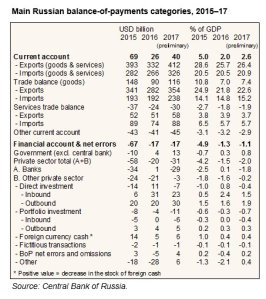

Exports measured in rubles, which is what our producers and workers really care about, are also up, and we continue to run a positive trade balance. We are particularly encouraged by our agricultural sector, where productivity, total output, and exports are all up significantly.

There are, of course, risk factors we need to manage, in particular, vulnerabilities in ou

Russian foreign trade continues to recover; capital outflows up slightly. Source: BOTFIT

r banking system. The RCB had to nationalize three banks last year, and there are others that may need to be rescued this year. But on the whole, the financial sector has held up, thanks again to aggressive RCB action.

We also need to keep a close eye on the solvency of regional and local governments, which have been struggling since 2014, in part because we made a decision at the federal center to pass some of the costs of the recession down the federal chain.

Another important risk factor is the possibility that capital flows, which were overall positive in 2017 but turned sharply negative in the second half of the year, may accelerate with new rounds of Western sanctions, particularly the new U.S. sanctions expected in February. But the economy has held up in the face of other capital outflow surges, and we expect it to do so again should it happen after February.

In sum, we have every reason to believe that Russia has weathered the economic shocks of 2014. In part, we can thank higher than expected oil prices in 2017. But most important has been prudent and professional macroeconomic management. Most importantly, we have witnessed a slow but steady diversification of the economy since 2014. A lower ruble has made Russian goods and services more competitive on domestic and foreign markets, and the strengthening global economy will help exports going forward. We are accordingly less vulnerable to another oil shock, as unlikely as that might be given global growth. If current trends hold up, we may be able – eventually – to put the curse of oil/Dutch disease problems behind us.

Regardless, the particular character of our political economy reduces the likelihood that external shocks and/or the occasional recession lead to mass unrest. Above all, we have a very flexible labor market. When necessary, enterprises can reduce wages rapidly, shorten working week, send workers out on unpaid leave, reduce working hours and production rates, or even accumulate wage arrears) without losing employees. The reason is that workers have little choice when other enterprises are also reducing wages or accumulating arrears, and they are otherwise constrained by low housing mobility. They also often receive various forms of non-wage compensation from their employers, all of which helps keep them on the payroll.

This flexible labor market, along with a central bank that reacts to downtowns with aggressive monetary stimulus and adjustment through ruble depreciation, means that recessions don’t produce mass unemployment or widespread enterprise bankruptcies. Economic pain is thereby distributed relatively widely, or at least more widely, and less arbitrarily, than would be the case with “normal” Western-style contract labor.

The downside of this arrangement is that recessions produce less restructuring than would be the case otherwise, which is one factor inhibiting higher trend growth (along with others such as a weak rule of law and endemic corruption).

Nevertheless, we are likely to see trend growth of at least two to 2.5 percent going forward, which should be enough, all things being equal, to head off some kind of popular uprising that produces a “colored revolution” that, once again, allows our adversaries – and enemies – to take advantage of our weakness.